PlusNews, the global online HIV and AIDS news service of the United Nations Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN), has published an excellent in-depth analysis of criminalisation in Africa.

A collection of short articles focusing on various aspects of criminalisation in different parts of the continent can be downloaded as a pdf here, or read online here.

They include:

- Cameroon: Whose responsibility is HIV transmission? examining the issue of moral and legal responsibility and focusing on Cameroon.

- Mozambique: Proposed law a mixed bag for people with HIV, examining the specifics of Mozambique's proposed criminal HIV transmission laws.

- Southern Africa: HIV laws put women in the line of fire, examining laws in Botswana, Malawi, South Africa and Tanzania, and proposed laws in Angola and Mozambique.

- West Africa: HIV law "a double-edged sword", examining the laws in Benin, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone and Togo.

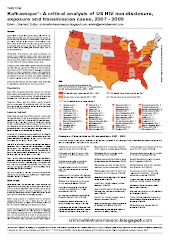

I reproduce here an article providing an overview of the situation alongside

a criminalisation map of Africa which they say will be updated once they receive more accurate information from readers in Africa.

AFRICA: Will criminalising HIV transmission work?

IRIN/PlusNews

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa are looking at a new way of preventing HIV infections: criminal charges. But experts argue that applying criminal law to HIV transmission will achieve neither criminal justice nor curb the spread of the virus; rather, it will increase discrimination against people living with HIV, and undermine public health and human rights.

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa are looking at a new way of preventing HIV infections: criminal charges. But experts argue that applying criminal law to HIV transmission will achieve neither criminal justice nor curb the spread of the virus; rather, it will increase discrimination against people living with HIV, and undermine public health and human rights.

UNAIDS has urged governments to limit criminalisation to cases "where a person knows his or her HIV-positive status, acts with the intention to transmit HIV, and does in fact transmit HIV". The reality is that intentional and malevolent acts of HIV transmission are rare, so in most instances criminal prosecutions are not appropriately applied.

In Switzerland, a man was sent to jail earlier in 2008 for infecting his girlfriend with HIV, even though he was unaware of his HIV status, and a Texas court recently sentenced a man living with HIV to 35 years in prison for spitting on a police officer, although the chances of the officer being exposed to the virus were negligible.

Laws making HIV transmission an offence are not new to the developed world, but the trend has been growing in African countries, where higher prevalence levels make such laws all the more attractive to policymakers.

"Africa has burst into this whole frenetic spasm of criminalising HIV," said South African Justice Edwin Cameron, who is also HIV positive, at the International AIDS Conference in Mexico earlier this year.

In Uganda, proposed HIV legislation is not limited to intentional transmission, but also forces HIV-positive people to reveal their status to their sexual partners, and allows medical personnel to reveal someone's status to their partner.

Most legislative development has taken place in West Africa, where 12 countries recently passed HIV laws. In 2004 participants from 18 countries met at a regional workshop in N'djamena, Chad, to adopt a model law on HIV/AIDS for West and Central Africa.

The law they came up with was far from "model", according to Richard Pearshouse, director of research and policy at the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, who maintains that the model law's broad definition of "wilful transmission" could be used to prosecute HIV-positive women for transmitting the virus to their babies during pregnancy.

People living with HIV have expressed concerns that the growing trend to criminalise HIV infection places legal responsibility for HIV prevention solely on those already living with the virus, and dilutes the message of shared responsibility.

UNAIDS has warned that using criminal law in cases other than intentional transmission could create distrust in relationships with healthcare workers, as people may fear the information will be used against them in a criminal case. Such laws could also "discourage HIV testing, since ignorance of one's status might be perceived as the best defence in a criminal law suit."

Some policymakers have called for HIV legislation as a means to protect women from HIV infection, but the irony is that sometimes these laws may result in women being disproportionately prosecuted. Many women find it difficult to negotiate safer sex or to disclose their status to their partner.

What are the alternatives? UNAIDS recommends that instead of applying criminal law to HIV transmission, governments should expand programmes proven to have reduced HIV infection. At the moment, there is no information indicating that using criminal law will work.